Admittedly, it's a bit odd to see a biography of a professional wrestler on this site. That "activity" is something of a combination of sports and entertainment, and the latter is more important than the former.

For an explanation, let me go back to 1970. I had just moved to the Buffalo area as a teen, and pro wrestling was shown weekly on television. I enjoyed the action and the story lines, mostly because of the campy approach. My friends and I even went to a few matches. We may have been laughing at them or with them in a given moment, but our money went into their cash registers all the same.

Meanwhile, up iu Toronto, "The Sheik" was holding court at Maple Leaf Gardens on many a Sunday night. Television station CFTO had the longest sportscasts in history back then, and sometimes would run film of the entire main event of the wrestling card. That was great exposure for the business and the Sheik, who would somehow figure out a way to avoid losing, match after match. He might have come to Buffalo for the odd match, but I'm not sure if I saw him live.

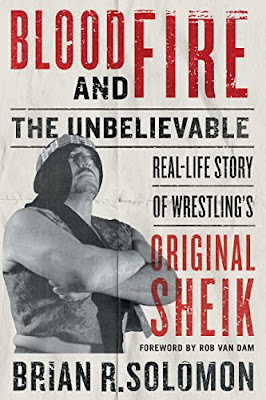

Therefore, the chance to read "Blood and Fire" - a biography of the fabled villain - was too good to pass up. What was the story on that guy who usually wound up bleeding all over everything but still managed to avoid losing by a pin? Brian R. Solomon, who has worked for several wrestling organizations over the years, has some answers in his book.

We start, as we always do, with the name. Eddie Farhat was just another guy from Eastern Michigan who had spent some time working in the auto factory before thinking there had to be a better way. He turned to wrestling, and found the gimmick that made him relatively famous. Ed dressed up in Arabian clothes, complete with pointed shoes, picked up a "prayer carpet," said he was from Syria, and was off on his new life. That's a major transformation for a Catholic, but it worked.

The Sheik was quite a villain. He always kept an air of mystery around him, mostly by a willingness to stay in character in almost all situations. The Sheik also was all in when it came to selling that image. He never spoke, either on television or in person. The Sheik had a manager along to do the talk when necessary. And in the ring, his ability to drive the emotions of the audience higher and higher often meant that he had to give a little slice to an forehead or arm - sometimes but not always his own - in an effort to raise the temperature of the audience via some spilled blood. As a promotional tool, it worked quite well. He was the man many loved to hate.

This all came with a behind-the-scenes catch. The Sheik was wrestling in a time when the business was cut into regional territories, lightly brought together in a national organization. That's why there seemed to be 57 world champions in the United States in a given moment. You could say the business sort of resembled organized crime in its structure. The catch is that the boss of the Detroit region was, yes, Farhat himself. When you are the boss and can plan the results, you probably don't want to prearrange a loss (although it could be argued that the occasional defeat might have been good for business). It turns out some of the wrestlers ran territories as well.

The Sheik had quite a ride for a while. He appeared all over North America, and made some lucrative stops in Japan. However, eventually the territory system started to blow up, and Farhat was known to spend money as fast as he earned it - if not faster. Eventually, the regional promoters fell by the wayside, leaving the WWE as the only major financial player in the field. Still, the Sheik soldiered on, wrestling until he was close to 70 years old - even if the matches were very short. Once he quit, his health quickly turned for the worse. He died at the age of 76 in 2003.

We have to salute Solomon for his level of research here. It couldn't have been easy to delve into this man's past. Many of the family members are dead or are unwilling to talk. That leaves something of an outside-in approach to biography. He talked to a number of people who were involved in wrestling in that era, who all seem to respect the Sheik if they never knew what he would do in a given moment - even in the ring itself. And how did he find all of the results of so many of matches. Solomon deserves plenty of credit for this.

One fun part of the book is that some of the back stories of the wrestlers of that era come out. Consider that the Sheik took a look at his oversized gardener, gave him some lessons, and called him "J.B. Psycho." Heck, Chief Jay Strongbow was Joe Skarpa, an Italian American from Nutley, New Jersey. The Mighty Igor, practitioner of "Polish Power," was Dick Garza, an Hispanic American. And so on. But of all of them, the Sheik was the one who did the most to push forward the idea that watching half-nelsons applied for a few hours could get dull, and that the act needed a little chaos to keep the customers entertained. That theory still drives some of the business to this day.

I'm not the usual reader for a book like "Blood and Fire," since a long magazine article might have satisfied my curiosity on the subject. It probably could have lost some pages quite easily, as the details of matches from 50 years ago feel a little irrelevant these days. But it's still fun to get the full story of Ed's life, while marveling at the effort to put it together. And those who have an interest in pro wrestling - and in particular in that era - will find plenty to enjoy.

They don't make them like "The Sheik" any more.

Three stars

Learn more about this book. (As an Amazon affiliate, I earn money from qualified purchases.)

Be notified of new posts on this site via Twitter @WDX2BB.